Human endeavours are pursued in environments. Whether man-made or natural, environments have been the subject of scientific investigation and discovery since the early days of mankind.

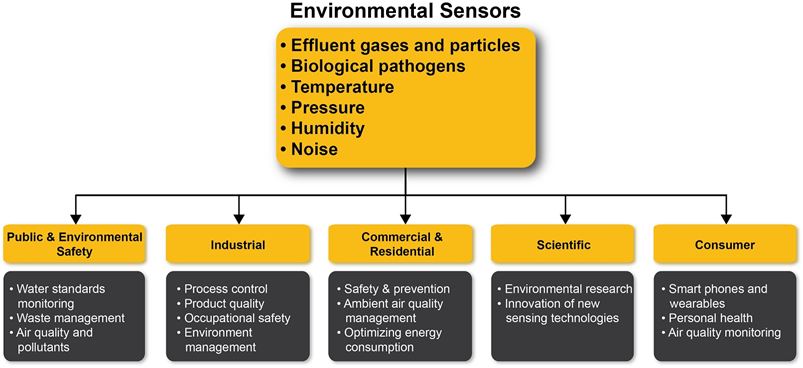

Populations across the globe are seeking ever more information about the places where they live, work, and prosper – not only to effectively protect the environment but also to understand the risks and impacts of these environments to human health, safety, and general living. In addition, melting icecaps, sinking shorelines, rising global temperatures, etc. have served as observable consequences of human progress on the delicate and complex harmony underlying our planet’s environment. Now taking an unprecedented interest in environment related issues has become a priority of scientists, policy makers, and even ordinary citizens. Complementing this increased awareness of our ecology and habitats, new sensor technologies and sensor networks are making environment related information easy to collect and disseminate. While many sensing apparatus have been used for decades in specialized applications, dramatic reduction in cost points are making environmental sensing increasingly accessible to anyone, and they are now being used for even mundane domestic applications. The figure below delineates the general sensor technologies available in the marketplace that are being implemented in environmental applications as well as in a variety of personal/commercial applications. A combination of sensors are increasingly being embedded into smart devices like phones and wearables to bring unique insights and personal measurements that change the way we perceive not only our environment but also ourselves.

Figure 1: Sensor Types and Categories

In this article, we focus on the environmental applications of sensor technologies and the key trends that make up this dynamic and growing market.

Environmental Sensing Technology & Application

Sensors and measuring devices have become indispensable in practically all branches of industry and modern life, and society has witnessed their widespread use in environmental applications ranging from simple carbon monoxide detection at home to complex assessments of road conditions. Environmental sensor applications constitute five distinct domains as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Application Domains of Environmental Sensors

In all these domains, the fundamental task of sensors is to measure the concentrations of metals (Lead, Iron, Magnesium etc.), radioactive substances (Radium, Uranium, etc.), gases (CO2, NO2, Ozone, CO etc.), organic compounds (Benzene, Methane), and biological pathogens (algae, bacteria etc.). In addition, measurement of pressure, humidity, and temperature are common. A wide variety of semiconductor based sensing technologies are now available in increasing small form factors, and most of them operate as passive or active. A passive sensor does not need any additional energy source and directly generates an electric signal in response to an external stimulus. Thermocouples, photodiodes, and piezoelectric sensors are all typical passive sensors. Active sensors require external power for their operation.

See related product

See related product

In almost all cases, sensors are components in a larger control or measurement system, and the sophistication and sensitivity of the sensor system increasingly relies on software based interpretation and analytics of sensor signals. Regardless of sensor type, the sensor industry is experiencing an explosion in applications as both the lower costs and higher functionality are making sensors valuable in all domains.

Major Trends in Sensing

As the digital revolution of the last three decades continues, sensors have come to the forefront in facilitating a new era of applications. The Internet of Things (IoT) paradigm particularly relies on sensory inputs and analytics to drive new sources of value to stakeholders. Continuous innovation on a variety of fronts is driving a few major trends in sensor technology:

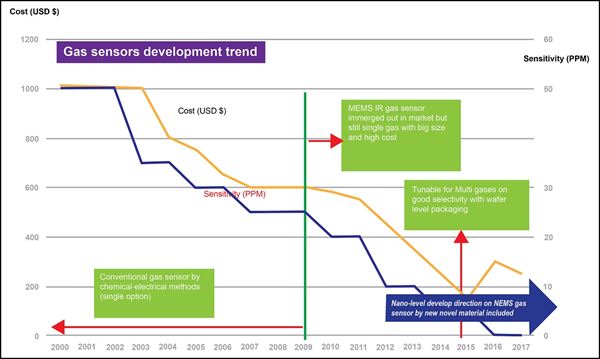

Sensor performance: The performance of a sensor is a function of the sensitivity, accuracy, and reliability of its output signals. Innovation related to new materials, sensing techniques, fabrication, and packaging techniques have all contributed to not only significant reduction in costs but also to the improvement of sensitivity. As an example, just in the last two decades, gas sensor sensitivities have improved from 50 ppm to about 10ppm. In the same time frame, the unit cost of gas sensors has decreased almost three orders of magnitude (Figure 3). The increased tendency to include microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and more recently nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS) in sensing devices has greatly enhanced the accuracy and reliability of sensors. Furthermore, the increasing use of silicon measuring elements (also for calorific and chemical parameters) has led to the increased capability of sensors. Simultaneously, measurement uncertainty is also being decreased through optimized packaging technology, thereby enhancing reproducibility and long-term stability even in intensive applications. The trend towards greater performance will bring in hyper-sensitive devices that will find application particularly in early detection systems driving enormous cost-avoidance schemes in industrial, commercial, and personal settings.

Figure 3: Cost and Performance Trends in Gas Sensors (Source: Prof. Jeff Funk, New Generation MEMS Gas Sensors)

Miniaturization: Remarkably, the increased performance of sensors has been achieved while simultaneously reducing the form factor and power consumption requirements of the sensor. For example, over the span of four decades, gas sensors have gone from being as large as 17mm to less than 2mm (Figure 4). Notably, unit power consumption reductions by over 2 orders of magnitude have accompanied these form factor shifts.

Figure 4: Miniaturization of Gas Sensors (Source: Professor Jeff Funk, New Generation MEMS Gas Sensors)

The small sizes and lower power characteristics are driving increased portability, and they are also extending the life of sensors. Without the need to rely on line power, battery powered sensor systems are now enabling new monitoring paradigms. Sensitive industrial areas and environments where power is scarce can now be monitored with the most minimal footprint. Silicon based sensing is ensuring the trend of miniaturization that has brought about dramatic changes in computing power (Moore’s law) will also be a mainstay for sensor technologies. By far the biggest benefit of miniaturization is the ability to embed sensors in wearable and smartphone technologies.

Figure 5: Environmental Sensor Shipments in Handsets and Tablets (Source: IHS Emerging Sensors in Handsets and Tablets Report – 2014)

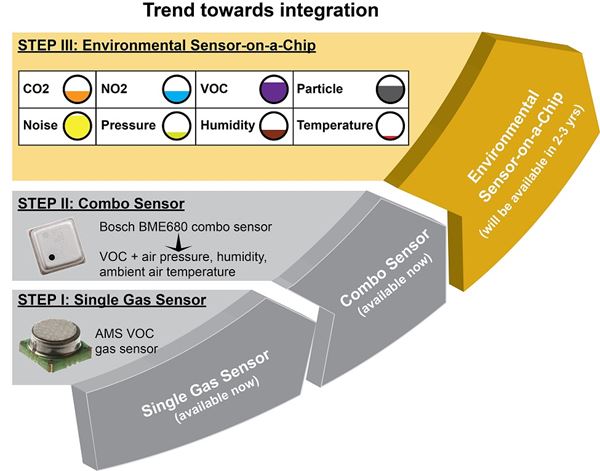

Integration: Another technological trend underway is the use of multiple sensors in a single device for mass applications. Integration of numerous sensors into a sensor array e.g. on a hot-plate in conjunction with pattern recognition is driving new devices that do more than one type of sensing. Detecting multiple gases and also detecting physical environmental conditions like temperature, humidity, and pressure are now feasible capabilities, and they are finding use in commercial and personal applications. The coupling of physical, chemical, and biological sensors on a single sensor element e.g. for pressure measurement, acidity measurement etc. is changing the nature of laboratory work. An “environmental sensor on a chip” type device is no longer just a concept and has the potential to dramatically speed up environmental sensing and dramatically reduce the cost of analysis.

See related product

Figure 6: Integration of Various Environmental Sensors

Standardization and Security: Since sensors are always parts of broader control systems, the ease with which a specific sensor or a module with multiple sensors can be integrated into the broader system is crucial. In addition, with so many sensors all sending data continuously, the need to have interfaces that help harness the data is vital. Standardization in connectivity and communication protocols is clearly necessary, as cross domain data interchange provides valuable insights. Furthermore, system on chip designs that integrate sensing modules with standard power, processing, and RF modules are becoming increasingly prevalent. This model of design and communications standardization reduces cost, device size, and power consumption while increasing device functionality and application scope.

Figure 7: Integrated Environmental Sensing Nodes

A significant benefit of standardization is also security. With a wide range of security threats affecting all digital networks and devices, it is crucial that sensors and sensor networks not be sources of vulnerability. Adhering to established standards ensures that sensor outputs are not manipulated and that only authorized receivers can receive sensor output.

Autonomic and Intelligent: As highly capable sensors proliferate around us, there is no doubt that we will be able to better understand much about our environment and the changes that occur within it. Sensor devices are being improved rapidly to achieve autonomic and more intelligent operational modes. The key to such operational efficiency is in appropriately processing the sensory data. True insights often require bringing together data from multiple sources. In addition, trended data is often more valuable than point measurements. To achieve this mode of operation, increasing functional integration based on highly integrated components in sensor electronics is already being explored. Pattern detection, additional data acquisition, and advanced algorithmic analysis are crucial to take sensor data to the next level. To this end, sensor devices are increasingly equipped with on-board analytics, and they can also connect to cloud platforms to derive new insights. The sensor device itself is increasingly embedded with capabilities like self-monitoring, interference detection and diagnosis, self-calibration (self-adjustment), and reconfiguration. Using these capabilities to drive preventive maintenance has the potential to result in dramatic reductions of operational cost in industrial and commercial settings. Another area where sensor devices are progressing is the usability and implementation ease (for integrated communication interfaces, plug and play capabilities, auto localization, etc.) to adapt to the context of the environment.

Achieving an autonomic yet highly integrated operational mode requires a very holistic approach to sensor design, one that involves the utilization of novel 3D design tools, FEM (finite elements method) computation, Matlab/Simulink integration, and the use of comprehensive and exact material data. Furthermore, fusing data obtained from different physical sensors to provide more comprehensive information from a single “logical” or “virtual” sensor is a key area being targeted by sensor innovators.

All the trends above will change our world in unprecedented ways. Together, developments in cloud computing, sensor technology, wearables, and smartphones are likely to result in a heightened awareness of the environments in which we live, work, and play. It is not hard to conceive a world where sensor networks deliver information about air pollution levels, road conditions, noise levels, weather conditions, radiation levels, and water quality of our immediate environment directly to our smart phones. While these are all urban applications, there is an equally large set of data streams that will be available in the wilderness and in environmentally sensitive areas like forest fire detection, ozone level detection, ice melt rate detection, salinity etc. All this information will enable us to not only control environments but also to understand them in new ways.

Summary

Environmental sensors are crucial in making a more connected world possible. From providing information on our immediate surroundings to helping us tackle global climate change, sensors and sensor networks are fundamentally changing our awareness of the environments around us. Environmental, industrial, commercial, and personal spaces are all utilizing ever smarter sensor devices to drive new approaches to safety, control, and monitoring. Sensors themselves are undergoing new developments along a variety of dimensions – sensor capabilities are rapidly expanding while simultaneously improving accuracy and reliability, sensors are becoming smaller and smaller in both power consumption and form factor, multi-sensor devices are becoming more commonplace as devices are being deployed in a broader scope and new levels of integration between multiple sensors and other components are affording new possibilities. A future where sensors are autonomic and intelligent is clearly viable and will bring with it new possibilities not only for operational efficiency and cost reduction but also for the development of new capabilities to protect human health, safety, and the general wellbeing of our planet.